9/26/2023

You can stream the podcast of this episode above. To listen to this podcast on your podcast app just visit remedialpolymath.podbean.com/ and click on the app you use.

I need to start this by sharing something. I researched this topic for a long time, too long, and I found myself meandering on a journey of information overload. Weeks of work went into this. It is twice as long as my other episodes and took a lot of rewriting and rethinking. I was confused. I started to explore seafood, the history, the health, the future, etc. I wanted to explore what most find a “boring” topic and expose it as truly fascinating and informational. Don’t worry, it is still that. (I write these out beforehand, can go to website to read the formal document, see references, etc.) But, to be sincere, I end up using a lot of sentences that start with “I,” and I often address the reader directly. Instead of presenting revealing information and leaving you to come to conclusions, if you even have any, I am more forward in my thoughts on the matter. That wasn’t the initial idea, that’s not what I’ve aimed for so far in this show. But that’s the way it turned out for these episodes. That’s the way it needs to be. You’ll soon find out why.

It also might help to explain that this will not be your average story where I load you up on sadness about the sad loss of the living creatures of the ocean, all driven by human greed. Sure, there is plenty of that sprinkled in. But it wasn’t my takeaway after all of this, I ended up seeing things differently and try hard to explain what I see as the the philosophic underpinnings behind the wildness that is humans fishing on planet earth. I grew up near Lake Michigan, I live inland now, I prefer salt-free water, I don’t eat fish, nor have any connection to the creatures of the ocean. Yet, I saw how these issues affect everyone. If you’re like me this episode applies. You don’t have to be a seafood loving, ocean-side person for this to be relevant to you. That’s why I made it.

You see, I already had an interest in seafood. Then I learned a sliver of the information I am about to hurl at you, and I was sold on diving deeply into the subject. I still worried many might, at first glance, not find it a subject worthy of understanding thoroughly. But oh my, is it ever.

Not only is it worthy of being understood. I now know it’s necessary.

We will explore what we are doing to our oceans, the creatures that call them home, and how that affects you immensely, no matter what you eat for dinner or where you call home. We will examine the history of eating water creatures. That will show how this endeavor hasn’t always been handled as it is today, even when eating water creatures was. In fact, the differences in approaches between modern times and the past are night and day, technological advancements aside. It’s utterly fascinating. We will get to exploring ocean health and look at what’s happening in the environment that, you know, is the majority of our planet and simultaneously the environment we don’t call home and the environment that provides for life for everyone regardless of where they live or what they eat. We will discuss the health positives and negatives surrounding seafood and give you some actionable information. We may even have a little fun. But mainly, just as it was in my weeks of doing research for this and thinking about how to explore this topic, we will attempt to have a holistic understanding of many aspects of the complex system that is seafood. By the end, I hope you’ll feel better informed about this deceptively important topic for many reasons.

All of this needs to be talked about. This topic undoubtedly needs to be understood from as many angles as possible. Because governments and even environmental groups are ignoring what is genuinely happening or doing a crap job of addressing it. And more importantly, there are ways out of this. We can start addressing this issue tomorrow and probably eventually fix it. We just need the motivation to do so. But motivation without information is a big ask.

And the advice will not be to just stop eating fish, although that tactic may have my vote and needs to be discussed. One must stay realistic, though. Suggesting the extreme often leads to complete inaction. Once we go through this journey, you’ll see there is a way to have your fish and eat it, too. More on that later…

Remember that the purpose of Remedial Polymath is to explore topics deeply but in a universally understandable way, see if a rigorous understanding turns any assumptions on its head, and maybe humble and entertain along the way. As always, stick with me until the end. Pretty please with whipped cream and a cherry on top. Your brain will be happy you did, even if a lot of the information leaves you anything but.

So…. Let’s evaluate seafood.

I didn’t expect this seemingly bland topic to impact me in the way it did. I did not foresee coming away with such strong sentiments about the manner in which we remove protein from the seas. My brain didn’t want to present such strong views, so I initially endeavored to be balanced. Here is the thing: when I explored seafood, I eventually realized I was researching a deep corruption within our midst. I discovered people look at this food source incorrectly. There is a corruption with dire, worldwide implications that touched issues unrelated to caloric needs. Then, I learned about the health issues surrounding those calories. It was downright confusing, and it simply didn’t compute.

There is an appalling slow global suicide occurring right now in the waters all around us. I might use a synonym for suicide if one existed to be less dramatic and not turn you off from hearing more, but there aren’t any. So, if I seem overly passionate, it’s because what I learned frankly affects everyone. It matters not where you live or what you eat.

It was hard not to think that what I learned while looking into fishing is the most significant story concerning our world that no one is talking about. It needs to be shared, understood, and acted upon. Share this episode with others. Take a further look into it. People need to know about this and what they’re supporting with their innocent ignorance, dollars, and dinner choices. Okay, now that the public service announcement is out of the way, let’s take a deep dive into all things seafood.

As you can already surmise, this is part I of the episode. I didn’t intend for this to be so lengthy, but it is, so I split it up. In this episode we’re going to take a look at why this topic is so surprisingly important, no matter what you eat or where you live. We’ll look at the history of seafood and fishing, which will surprise you. We’ll look at what we’re doing to the oceans and the implications of that. We’ll touch upon what can be done, what should be done, and why. Next episode we’ll jump into the health of seafood, which is again surprising, and not in the way you may expect. We’ll evaluate the situation as concerns many of the types of seafood you probably enjoy, in terms of health, sustainability, ways to get yourself the best kinds, etc. And we’ll talk about the effects of oceanic pollution and what to do about it. Among other topics. So, yeah, there will be a lot more coming at you in part II, just know that.

An Introduction to the Serious Issues Surrounding Food from the Seas.

Let me tell you a true story.

In the 20th century, the waters off the coast of Somalia were teeming with marine life, providing vital sustenance and income for the coastal communities. Fishing was a way of life for many, and the sea’s bounty supported families and local economies and was an underpinning of their culture. However, they soon found many unwanted foreign visitors armed with modern equipment.

These foreign vessels, driven by the demand for seafood in global markets, began exploiting Somalia’s waters with little regard for conservation or local livelihoods. Industrial-scale trawlers and illegal fishing operations plundered their seas, quickly depleting fish populations and leaving local fishermen struggling to catch enough to support their families calorically. As fish stocks disappeared, jobs and food disappeared, desperation grew, and the people couldn’t reliably keep their children’s stomachs full. Many then turned to what they saw as their only last resort: piracy.

The economic desperation fueled by the collapse of the fishing industry had far-reaching implications. With traditional livelihoods eroding, coastal communities faced hunger and poverty. The lack of alternative economic opportunities led many to try to extract wealth from the fancy vessels they saw sailing past their shores. Pirates, once fishermen themselves, began hijacking the very commercial vessels that they saw as the initial cause of their despair. As these ships would pass through their region, they would storm the boats and then hold crew members for ransom, demanding payment for their release.

The piracy crisis profoundly impacted the region’s stability, affecting much more than coastal fishing communities. Somalia’s central government was weak and struggling to maintain control, and the piracy problem further eroded its authority. Foreign naval forces intervened to curb piracy activities and protect international shipping routes. While aimed at strengthening security, these interventions also led to clashes and confrontations with local communities, exacerbating existing tensions and giving more power to questionable figures. We know how things ended, as Somalia is now considered a failed state.

The story of Somalia’s fishing industry collapse is a stark reminder of the interconnectedness of environmental, economic, and political factors. Unsustainable fishing practices, driven by profit and disregard for local needs, devastated marine ecosystems and contributed to poverty, piracy, and political instability. The situation underscored the importance of responsible and sustainable management of marine resources and the need for international cooperation to address global challenges.

The story of Somalia serves as a cautionary tale about the consequences of ignoring the delicate balance between human needs and the health of our oceans. It highlights the urgent need for sustainable fishing practices and the recognition that the choices we make in managing our marine resources have far-reaching impacts that extend beyond the boundaries of the sea. The introduction of modern fishing vessels and tactics, caring not how or what they took, helped push Somalia into collapse.

Let me tell you another true story.

In the 19th century, the town of New Bedford in New England experienced a period of unparalleled prosperity driven by the whaling industry. The town’s economy boomed as its whaling fleet dominated the seas. The streets were lined with opulent mansions and bustling businesses. This place was straight-up rich. It was the Silicon Valley of its time, with VC-like investors backing more and more whaling ships. The promise of immense wealth drew many. Even simple deckhands on these ships made substantial wages when a successful hunt was achieved, coming home with loads of cash that they injected into their community.

Whales were prized for their blubber as it is rich in oil that could be rendered into products like lamp oil, cosmetics, and soap. This oil was a vital resource in an era before electricity, and it fueled the lamps that illuminated homes and streets. It seems pretty odd today, imagining people looking to ocean animals as an energy source for street lamps. It illustrates a possible future in which our current practices could be remembered as self-destructive and foolish. Either way, whales were hunted ruthlessly, with little regard for the long-term consequences of depleting their populations.

While New Bedford flourished, whales became the target of relentless exploitation. You can predict what happened: the pursuit of profit led to overfishing on a massive scale. Whaling ships crisscrossed the entire world, often spending years at sea, searching for profits concealed within the bodies of our oceans’ most enormous creatures. This intense hunting pressure decimated whale populations, bringing several species to the brink of extinction. Sadly, it drove a few species to a complete end. The Atlantic gray whale, the Pacific gray whale, the North Atlantic right whale, and the Caribbean monk seal were all extinguished for their fat. Due to our desire for their blubber, these animals will never be seen again. While we can’t know for sure, it is estimated that many whales worldwide were hunted down to just a few percentage points of their former populations. By the late 1800s, the once-abundant whales were becoming scarce, the industry that had brought prosperity to New Bedford was collapsing, and the whole region’s economy declined.

The decline of the whaling industry had far-reaching economic and cultural consequences for New Bedford. The entire region’s economy suffered a severe blow as the supply of whales dwindled. Ships returned with smaller and smaller hauls, and the once-high wages for all the sailors began to dwindle. The grand mansions that had once symbolized the town’s wealth fell into disrepair, and the bustling streets grew quieter.

Faced with the reality of an industry in decline, the residents of New Bedford turned to a new and more sustainable seafood source: oysters. The town’s natural harbor provided an ideal environment for oyster farming. Oysters were abundant and relatively easy to cultivate. They embraced this new path and decided to alter how they viewed the ocean regarding food and money. It offered a steady source of income for those who shifted their focus from whaling to oyster farming. Maybe overnight fortunes weren’t being made, but a healthy and long-lasting economy emerged.

The story of New Bedford serves as a stark warning about the consequences of unchecked overfishing and the importance of sustainable resource management. Humans threatened the entire population of cetaceans, all types of whales everywhere, with the technology of the 18th and 19th centuries. Imagine what we are capable of today…

However, this story also underscores the potential resilience of communities in the face of changing circumstances and the potential we have to change our ways for the better. The shift from whaling to oyster farming revitalized the town’s economy. It contributed to the conservation of all marine resources in the region. The entire ecosystem was made healthier.

Today, as we face similar challenges with the overexploitation of seafood resources, the story of New Bedford serves as a reminder that principles of sustainability and responsible stewardship of our oceans must guide our approach to catching and consuming fish. We must have sound first principles underlying how we approach the seafood industry. Even if one is driven by greed, this still applies!

A Quick Look At What’s Going On In Our Water

I tell those two stories to exhibit two different reactions humans have had to errors made in our relationship with seafood. Regional collapse and the reemergence of piracy due to these errors sure is scary. So is almost eliminating the world’s largest marine animals from the planet. We’re not here to discuss pirates and whales, but their stories illuminate the weighty unintended consequences of mistreating our oceanic ecosystem. Because these examples are nothing compared to the potential results we are at risk of creating today. The threat is not regional. It’s global. It threatens a lot more than just the prevalence of a food source.

Let’s examine some rapid-fire information about what’s happening in our waters. Diving too deeply here and getting lost is easily possible, so we’ll try to keep it succinct while covering much ground. You just need to hear this near the beginning to better comprehend the scope of the big-picture situation we find ourselves in.

Here’s some data that’ll make you double-take. Recent studies project that wild-caught seafood may disappear by the middle of the 20th century. Yes, literally disappear. It will not be available in your grocery store if we keep up with current practices. About one-third of the seafood species humans hunt and consume have crashed. Those species risk becoming severely depleted or even extinct in a specific region or ecosystem.

Here is another wild projection. If we don’t change our ways in 30 years, plastic in the ocean will outweigh all marine life. That is just plastic waste. This isn’t a tree-hugging, politically-motivated hypothetical. It is pretty clear to see. Oh, and fish appear to like eating this junk or simply can’t avoid it getting into their systems for numerous reasons. When consumed, this waste does not merely move through the digestive systems of our seafood; it gets absorbed into the edible tissues. And unlike the land animals we consume, there is no way fish can avoid exposure. These waste products are within the medium of their existence. They’re literally swimming in it.

Estimates of how much seafood the average human consumes yearly are just over 45 pounds (slightly above 19 kgs for our international friends). Another related and consequential data point is that we eat twice as much seafood as we did 50 years ago. We’re doing twice as much fishing as we did as recently as the early 1970s. Isn’t that unexpected and intriguing? Remember that statistic.

We pull from our oceans, lakes, and rivers around 93 million tons of wild-caught fish every year. Not surprisingly, it is mainly from our interconnected oceans. Here is the horrible reality of our fishing efforts. It is calculated that an astonishing 38.5 million tons, or 41%, of what we pull from the water is known as bycatch. It is marine life we catch but did not intend to. Bycatch usually gets thrown back, and the fish are either dead when that happens, or they’re so affected by being caught via industrial-level trawling that they die soon afterward. It is vital to note that these numbers reflect what we know of within the legal side of fishing. Even then, it often comes from self-reporting, and one has to doubt they don’t fudge the numbers in their favor. Illegal fishing is, by its nature, tough to quantify. Still, reasonable estimates predict it is between 11-26 million tons annually. I will go out on a limb and guess that the more significant number is safe to work off of. Therefore, simple math tells us that illegal fishing – not including the bycatch – is about 1/3rd of all worldwide fishing. So, 1/3rd of the fish you eat, even in America or Europe (especially in Europe), is illegally caught on average. One doesn’t have to go to some sketchy market for this food; it often appears just like any other product in the store.

What else often gets caught in those massive nets as bycatch? Oh gosh, dolphins, sharks, turtles, birds, octopi, coral. The list goes on. Let’s examine the dolphins and sharks, though. These larger predators are paramount to the health of the entire food chain of the oceans, from microscopic organisms on up. Removing them will result in many predictable adverse outcomes and – maybe more importantly – numerous nonobvious and unknowable consequences. These are ancient creatures. These are intelligent creatures. They are the cleanup crew. Just think, there were sharks in the oceans before there were trees on the land. The oceanic ecosystems flat out do not remember operating without them.

It is estimated that up to 100,000 dolphins are caught in nets intended simply for tuna each year, along with an unknown amount of smaller unintended creatures. In the Indian Ocean alone, it is estimated that only 13% of the dolphin population that existed in 1980 is around today. It is not uncommon for commercial fishing boats to kill more dolphins or sharks than tuna fish when they do a haul. Imagine if you went to go deer hunting, and by pulling the trigger, you also ended up killing a bear, a wolf, and some squirrels. Would you still hunt in that manner?

Here’s the thing: It doesn’t matter what company you buy it from or what seal of approval it has. Companies currently have no will to commercially fish for just one species in a perfectly effective way. They probably wouldn’t catch enough to be commercially viable with today’s fishing tech and methods. One can understand that concern. However, looking into new tech and methods is something any industry should continuously be doing. The large companies with modern gear and fancy boats, hailing from Western countries, are also involved in this horrible bycatch reality. It is often unknowingly but sadly knowingly as well.

Another thing to consider regarding illegal fishing is where it occurs. It may not surprise you that it’s usually not off the coasts of wealthy countries where navies and coast guards roam (although that still happens). It is off the shores of poorer countries and regions where illegal fishing is rampant. But just like in Somalia, this does not mean those impoverished regions are at fault. Fishing is often done by companies from wealthier countries subsidized by their governments. In the process, they shoulder out local fishermen who can’t compete with the big boys. It destroys their economies and takes food – often calories necessary for their health and survival – out of their mouths.

This part is incredibly upsetting. All of us in the “civilized” world, through our taxes, are subsidizing the fishing industry to the tune of $35 billion a year. Without that financial lifeline, this industry wouldn’t be profitable or able to do the harm it does. And why are these governments doing this? For food security.

That’s right.

I hope I don’t have to give you any fancy statistics to convince you how laughable this is. How is it that countries, many of which are concerned about obesity within their populations, concerned about consuming too many calories, are able to justify these harmful subsidies? Year after year, we are gambling with our treatment of the oceans. And every year, the game inches towards a loss for both the ocean and humans.

I can now sense an understandable response that sounds like this: “Okay, okay, so we really need to improve commercial fishing. We need to rethink how we support and regulate this industry. We pollute too much. I get it, we all get it, but why freak out? We don’t live in the ocean. We don’t have to eat marine animals to survive. This response doesn’t seem balanced. What’s the point of this frantic grandstanding?”

A coherent response, maybe. But only if you don’t know the bigger picture. Let’s zoom out.

Consider the following two sentences.

The oceans, through the living creatures and plants within them, store 93% of all the carbon on Earth. The oceans, through the same creatures and plants, give us over half of the oxygen we breathe. It is estimated that phytoplankton, kelp, and algal plankton (primarily but not only) give us between 50-85% of the oxygen we breathe. One type of phytoplankton, Prochlorococcus, releases countless tons of oxygen into the atmosphere. Millions can fit in a drop of water. Prochlorococcus is probably the most abundant photosynthetic organism on the planet. Dr. Sylvia A. Earle, a National Geographic Explorer, estimates that Prochlorococcus provides oxygen for 20% of our breaths (one in every five breaths). They are abundant and resilient but also fragile in many ways, and just like other organisms, they rely on the oceanic ecosystem to thrive and create that oxygen that we all love.

We are quickly killing this complex system. The phytoplankton and algae in the oceans create massive amounts of oxygen and sink carbon in the case of plankton. Phytoplankton make oxygen and then consume carbon dioxide. Eventually, they die and sink to the bottom of the ocean, thereby sequestering carbon dioxide.

It’s interesting how trees and forests get a lot of attention in this regard. It’s not unwarranted, as rainforests are predicted to create somewhere around 28% of our oxygen. Still, the big picture tells a different story. When plants on land grow and live, they use large amounts of CO2 from the air. This is wonderful. We need them for this reason, among a myriad of others. No arguments there. However, people forget that when plants on land die – naturally or at the hands of humans – most of that CO2 is released back into the atmosphere by being burnt, decomposing, or being eaten by fungi, bacteria, or other microorganisms. The same isn’t true of the oceans’ ecosystems. The oceanic system is our best friend by taking carbon out of the air and keeping it out.

Without a healthy balance of fish, dolphins, sharks, etc., this life-giving and global-warming-protecting system is in jeopardy. Then factor in the pollution pressures on the ecosystem, and you can see the type of fire we’re playing with.

What most don’t know is that larger fish, the ones humans like to eat, and the predatory animals that end up in bycatch, feed on smaller animals than themselves (many of which humans don’t often eat as much), thereby keeping the number of animals that eat plankton and tiny organisms in balance. They also contribute significantly to the cycling of nutrients within the ecosystem. The waste products and decaying matter from these animals release nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus into the water, which are essential for phytoplankton (algae) growth. These larger marine animals act like a helpful spoon, mixing up the water and the nutrients found at different depths and helping balance out the population levels of all marine life.

We aren’t even totally confident of how marine animals, plants, and microorganisms stay in balance with each other. That means we aren’t sure what will happen eventually with our overfishing or how we can fix issues now or in the future. But let’s just use our logic: messing with the fundamental players in an ecosystem will lead to trouble. One intriguing and well-orchestrated study from Yale University measured how much carbon plants retain within a controlled marine ecosystem, both with and without predatory animals. The study found that 40% more carbon was retained when predators were present than when they were taken away. They found this was “owing primarily to greater carbon storage in grass and belowground plant biomass driven largely by predator nonconsumptive (fear) effects on herbivores.” Translation: when small herbivore fish have to worry about predators, they can’t eat plants until their heart’s content and less carbon is sequestered. I bring up this example not because it would be the main factor in our carbon sequestering and oxygen creation fears for the ocean (that would still probably be related to bacteria and phytoplankton) but because it shows how removing predator marine animals will affect the amount of carbon sequestering in ways that are just not obvious.

The complex marine food web, which includes predator-prey relationships involving fish, dolphins, and sharks, helps regulate the populations of different organisms. We need a balanced food web to support a healthy ecosystem and ensure that various species are present to contribute to nutrient cycling, oxygen production, and carbon storage. We can already see an unbalanced ocean food web and envision a destroyed one.

We will touch upon this point a bit later. Still, it’s essential to understand that most seafood is a resource, not a commodity. And just like in countless other examples through man’s history, when an asset isn’t owned by anyone, no one seems to care about taking care of it. This is called “the tragedy of the commons,” a term counted by Williams Forester Lloyd in 1833. Think about it for a second, and it will make sense.

The “tragedy” in reference here occurs when each individual perceives their actions as having negligible impact on the resource, assuming that others will bear the collective burden of responsible use. As more people adopt this mindset and exploit the resource, its capacity for replenishment becomes overwhelmed, leading to depletion, environmental degradation, or resource collapse.

So, for one, we’re up against human behavior. We’re also up against those who claim to help us. Just look at EII or The Earth Island Institute (I’ll just mention one right now, as this could also be an episode on its own). This environmental activist group (their words, not mine), among other things, tells us which tuna is “dolphin-safe .” I will ignore many other sketchy stuff they’ve been accused of. You can google that if you’d like. However, I will share that Sylvester Pokajam, who is the managing director of the National Fisheries Authority (which accounts for 20 percent of the world’s tuna catch), said, “There are no EII observers whatsoever, I am 110 percent confident, I know they don’t have observers, they are telling lies. They don’t have any program in place.” It’s not like he is the only person trying to warn people about the deception we face in the grocery store.

There is also the example of Mexico – wonderfully so – reducing their dolphin mortalities to historic lows by adding marine safety measures to their fishing practices. Yet Mexican fishing companies didn’t want to pay for this dolphin-safe label, probably because they felt they already met the standard and that supporting this group would be supporting dubious activities. The World Trade Organization eventually decided the “dolphin-safe” label unfairly discriminated against Mexican tuna as they were fixing their fishing practices yet still couldn’t get any recognition due to non-payment. The Earth Island Institute lobbied heavily against this decision.

I don’t want to be too much of a keyboard/podcast warrior here. But after looking into all of this, it doesn’t add up. It doesn’t seem like tuna are being protected. It does seem like consumers can easily be tricked. And “dolphin-safe” in no way means that dolphins are not being killed alongside your tuna. Just know that.

Okay okay. Let’s not get stuck in the weeds here. The important part is that tuna is still being decimated, and it’s hard to know who to support.

Some other “fun” information is that we trawl 3.9 billion acres of the seafloor annually by some estimates. I am told this is equivalent to 4300 soccer fields of seafloor every minute. These trawls can be as tall as a 10-story building. And it is like what it sounds like, we just catch up every damn thing possible in those nets, killing most of the creatures, and as the nets scratch and dig their way along, they destroy the habitats. Anything that isn’t commercially viable has a slight chance of living: turtles, fish that are too young, fish that are too small, coral, rays, dolphins, sharks, and even birds. I realize I mentioned this before, but I cringe at killing off creatures with incredible intelligence, such as dolphins and octopi, majestic turtles, or beautiful coral, just so we can take some of the catch home for dinner.

Here is the type of information that starts to hurt my brain. It is one thing to fish animal X to near extinction – that is the type of human behavior I’ve heard about my whole life – but in so doing, we are killing off animals Y, W, and Z, as well as essential habitats?! Again, it is understandable to protest that cows, pigs, and chickens live and die as they do. But when land animals are slaughtered for meat, you don’t accidentally kill off a wolf, a deer, a couple critical vultures, a squirrel, and a handful of plants and trees in the process. Not even in the most evil of factory farms. And sure, we can discuss methane from cows – let’s have the conversation by all means, but at the end of the day, the implications aren’t in the same ballpark.

This ecosystem is too valuable to risk. We are talking about a system that stores 20 times the amount of carbon that the forests of Earth do, an estimated 93%, while creating the aforementioned 50%+ of the oxygen we breathe. People call the Amazon the lungs of the world, but it’s actually the big blue. It’s the lungs of the world AND our best helper in fighting global warming-exacerbating CO2. I repeat this information because it’s worth repeating.

Okay, that was a lot of depressing news just thrown at you. It was chaotic and overwhelming. To be honest, I am not even confident I presented it well. There is too much. I do know that this information should startle you. It startled me. And that’s just a few paragraphs worth of information. We have plenty more to explore.

Actually, I take that back. This information should startle you. This information, what we will discuss, and what you just heard should make you furious. It should make you think about dinner differently, your world differently, your dollars differently.

Here’s the rub. Here’s what else I can’t stop thinking about. This isn’t like global warming. This isn’t akin to bitching about the CO2 exhaust from modern cars with catalytic converters. I believe humans are contributing to global warming, but let’s be honest: the world has experienced many times that were incredibly colder and warmer than it is now, and all that change occurred without humans. You can make an argument that we aren’t the main factor behind changes in the temperature. Or you can argue that we need fossil fuels and that drastic changes to our economies and way of life aren’t the correct path right now. It’s not my argument, but I understand it. We need ways to transport ourselves. Green energy doesn’t currently work everywhere and anywhere. We need to be able to turn the lights on. We do need industries for jobs, the materials of life, etc. There are at least good reasons, among the bad ones, that we create greenhouse gases. That is NOT the case regarding what we’re risking concerning seafood and the health of the oceans and, therefore, the world.

For that reason, maybe there is hope because this should be an issue anyone with any political leaning can understand and get behind.

We’re killing the oceans, we’re killing off the fish, we’re dismantling the ecosystem that takes out CO2 and gives us O2, and we’re polluting our water in ways orders of magnitude more tangible than any CO2 we release into the air.

This is bigger than the mistakes we make with fossil fuels.

It’s bigger than oil spills.

It’s bigger than slash-and-burn tactics in the Amazon.

It’s bigger than more powerful storms in the Gulf of Mexico.

It’s bigger than uncontrollable wildfires in Canada.

It’s bigger than the air quality in Mexico City.

It’s bigger than droughts in California.

It’s bigger than floods on the Yellow River.

It’s so big that it’s not really up for debate.

We are past that.

It’s paradoxically so big that most of us don’t even see it, talk about it, think about it, or know to do anything about it. It’s almost like we can’t see the elephant in the room because it’s an inch from our noses, and all we see is grey.

And why do we have this problem? Why are we losing this crucial planetary life support system?

It’s not because of overpopulation. It’s not for creating the fossil-fueled energy necessary for making the world go round. It’s not a regrettable side effect of creating the industries that give us lots of jobs, move us into a modern world, and give us the things that make everyday human life easier, enjoyable, and possible – regardless of whether we can accomplish that in a better way (we can). It’s not because we want nice things in our lives. It’s not because we don’t know exactly what we’re doing or agree on how to do it better. It’s not because we don’t have the technology to fix the issues yet.

Honestly (and this may seem downright odd), when you dig deep and consider everything from a 30,000-foot view, it’s not even really driven by greed. If greed was the motivating factor, then there are better industries, ones not subsidized into profit, to be in. It’s hard to understand, but greed is, in a messed up way, somehow a side effect of why we do this. Don’t misunderstand; greed plays a part in condoning this as a global community, but that’s not the initial “why” behind our endless and destructive search for seafood. It is frankly just ever so slightly downstream of the “why.”

This is the part that is hardest to grasp, but I think it is what underlies some of the overall weirdness of this situation. Let’s look at an even bigger picture than one concerning money – a made-up resource that is a relatively recent invention – and think about humans before all that. Human history is replete with instances of societies overhunting and gathering for preferred foods, often leading to resource depletion due to limited knowledge or care for sustainable practices.

If greed was one’s initial impetus, fishing is an odd business to pursue, especially in the West. It’s a difficult business, with difficult means of getting what you’re after. It’s messy, seemingly only profitable with subsidies. Oh, and by the way, the thing that makes you money is disappearing due to the way you go out and find it, and the only way to address that would be some kind of world cooperation that doesn’t currently exist. If it was pure greed, people would care about their money source more, wouldn’t kill it off, and wouldn’t think a little in the long term. If greed was the deep-down impetus that fuels the desire to fish, then it wouldn’t be an industry that doesn’t turn much of a profit – let alone break even – without the $35 billion it receives worldwide in government subsidies.

Greed isn’t the reason why the Japanese trap and murder thousands of dolphins and sharks each year, seeing them as competitors for what’s “rightfully theirs” – the fish of the seas. This is the most challenging aspect to wrap one’s mind around. Greed is complicated, can be hidden from ourselves, is dark, and is usually undesirable. When I looked at all of this information, I realized the real impetus underpinning the gross self-destructive system was so simple and unadorned that I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry.

Why in the holy hell of this beautiful world are we actively, knowingly, unarguably, and collectively committing this kind of global ecocide and potential suicide?

We’re doing it because we like the taste of water creatures.

That’s really it.

This behavior can be seen as related to an instinctual response to ensure the availability of familiar and favored sustenance. While profit-seeking plays a role, it’s worth considering that pursuing preferred food sources could be a more basic driving force behind overfishing, rooted in our innate biological and cultural inclinations.

This issue is so daunting not because we have to tackle greed. We actually can do that and have done so in the past. It is somewhat easier to address because we all recognize it as a negative attribute. Greed usually is handled by regulating or disabling the greedy people in question. This issue is a storm of craziness because we must tackle telling people they can’t enjoy the particular stuff they put into their mouths. Not everyone is darkly greedy. But everyone participates in, or at least wants to participate in, the endeavor of eating tasty things numerous times each and every day!

Let that sink in for a second.

Okay. The second’s up. Let’s change lanes a bit. As mentioned earlier, this episode would not just be destruction-porn. The collapse of the oceans was not the only reason I wanted to make this episode. There were others. One is more personal and amusing.

Now I will share a somewhat digressing, and totally irrelevant point in the big picture, that must be gotten out of the way in the name of transparency and fun. It is also part of the impetus for this article & episode.

I loathe seafood. I mean purely as food, not the actual creatures themselves.

It’s not that I just dislike the taste. I almost literally cannot be around it. I don’t wish to be in the same room as it. Fish markets are a personal no-fly zone for me, with mental fighter jets roaming my lizard brain, ready to shoot me down should I even accidentally enter the “air space” of deceased water creatures. Should my wife like to have some, it must be prepared and hopefully eaten outside. The aroma is that powerful to my senses. It makes me feel unwell. Don’t even think about cooking seafood in a pot and then rinsing it off and handing it to me for my meal. It must be power washed or, better yet, disposed of. I will taste it… That sounds like rambling hyperbole, but it’s my God-given cross to bear. However, after doing this research, I realize I have been released from the guilt of any personal involvement in this destructive system. In that way, it seems a gift I wish more were also given.

It is a wild and odd reaction action I’ve had all my life, and I am fully aware that it’s bizarre and childish. It’s a feeling that transcends a food preference. I dislike broccoli. We all have something like that. Broccoli has a texture and taste I do not find pleasurable. But I can be in the same room as broccoli. I can exist within range of its aroma just fine. Throw it into a soup with a barrage of cheese, and it becomes an enjoyable meal.

Not so with seafood (and I mean any seafood, not solely fish). It triggers something akin to a disgust and danger response somewhere within my subconscious. You might as well be asking me to consume produce left in a Chernobyl grocery store.

Please know that this is not something I am proud of, even though my previous words slightly make it seem otherwise. If there was a costly procedure I could undergo that would change this, I would consider it. Or at least I would have before creating this episode. I know I am missing out on a large swath of eating experiences, and I like to eat. I like to cook as well. I am missing out, and I know it. I looked into whether there was some kind of genetic variation I could have that would result in such an odd reaction – like how some eat cilantro and taste soap – but found nothing concrete, wondering if one day I could go through a crisper routine and be rid of this abnormality. Doesn’t look like that will ever be an option. I also looked up ways to overcome strong dislikes of certain foods. It’s mostly advice about exposure theory and different dishes and recipes. Yeah, I’ve been there. Done that. I don’t care how fresh the stuff is.

Sidebar: I am told that fish is good if it doesn’t taste ‘fishy.” That’s a red flag right there for the whole type of food.

I just ended up chalking this up to my Slovak and Irish genes. One-half of me blames the fact that half of my ancestors hailed from a poor, landlocked country. The other half blames the British for controlling my ancestors’ waterways, creating a small island (you know, those things surrounded by water on all sides) of people who often didn’t regularly eat the seafood that existed all around them. Even during famine, the Irish fishing rights were usually only for the landlords who often were absentee landlords who lived in England. But I digress. That’s better off a topic for a separate episode…

Anyway, I share those overly personal anecdotes to explain why I’ve always been deeply intrigued by this food and to partly explain why I wanted to do this deep dive. I wanted to know more about this food. This food that evokes such an odd reaction. I’ve often wondered how and why people eat this stuff?! I have wondered why we don’t just leave the world of water to the fish?! Didn’t we evolve out of that salty stuff for a damn reason?! Everyone has different tastes, but knowing how much the world likes this food source I cannot go near is like hearing that most people enjoy getting paper cuts on their cuticles. It doesn’t compute.

I had to know more. So voila, this deep dive was the result.

Outside of survival needs – we all get that – those questions have always nagged at me. It may come across as quite weird, but I genuinely marvel at how so many people look to the realm of salty water, the domain we animals decided to leave behind approximately 430 million years ago, the realm consisting of water we cannot consume nor survive in, a much-unexplored realm some say we know less about that outer space that is filled with alien creatures and unfathomable depths and untold secrets, for their food? Don’t people know we have used the oceans as our dumping grounds for quite some time? Don’t people know that is where so much of our everyday trash, industrial waste, agricultural runoff, and more radioactive waste than you ever like to think about ends up? Should we really be consuming its produce? What are the consequences for us, the oceans, the marine life, and the planet as a whole?

And, of course, what is the actual history of this practice we call fishing?

As is the case with most things, it is crucial – and downright entertaining – to examine the history of the subject before we digest the modern situation and implications. That will become a pattern on Remedial Polymath. Should that annoy anyone, my apologies. It truly helps to understand topics. Especially when details of the history may surprise one and ignite a reexamination of our current actions.

Maybe things have not always been like this…? Perhaps we can look to the past to inform our future…?

The History of Fishing

It may come as no surprise that fishing has been a part of human existence and a meaningful source of protein for some time now. Yet at the same time – and this might come as a surprise – many aspects of fishing are, in the scope of human history, a brand new thing. That’s worth repeating; fishing in how we do it is a brand-new endeavor. It is simultaneously an ancient and recent activity. Many of the relatively new aspects can be shocking when we eventually examine some of the statistics regarding how much we’ve been able to extract from our oceans in so short a time. But as always, as best as we can, let’s begin at the beginning.

The first evidence we have in which we can surmise our ancestors fished for food dates back to an astounding 500,000 years ago. We weren’t even Homo Sapiens yet, we were Homo habilis and Homo erectus. In archeological digs, we find fish fossils alongside those of the proto-humans that date from that period. However, that’s all the evidence we have. We know little else besides the fossils being found alongside human remains. I think few would doubt this is evidence enough that they fished. It would be hard to imagine that these “people” would not try to eat this food source that they could so clearly see existing in rivers, lakes, and the beaches of the oceans they lived near. It also would not be a stretch to think they could occasionally be successful at it. Suppose bears know the fish are there and that they’re yummy. Why wouldn’t our distant ancestors also attempt to eat them, regardless of their level of intelligence compared to modern man? All you would need to successfully catch a fish would be patience and your hands, a practice still used to catch catfish and some river fish in different parts of the world. Add in a crude spear, and it becomes even easier.

But of course, while that information is interesting, it isn’t too relevant to today’s discussion. But what is relevant appears a bit later, in the remains of a Homo sapien from around 40,000 years ago known as the Tianyuan man, whose remains were found near Beijing. There is evidence that he regularly ate freshwater fish. It is pretty well established that while people of that time probably lived a hunter-gatherer lifestyle and traveled around a bit, they did have some semi-permanent settlements. In what was perhaps their version of the garbage, we find discarded fish bones and cave paintings showing that they fished fresh and saltwater fish. In the south of France, some excellently preserved cave paintings are around 16,000 years old and clearly offer a variety of marine animals and scenes of hunting fish with barbed poles, which we would call a harpoon these days. It is pretty safe to say that seafood was a part of these peoples’ diets if they decided to immortalize it within their art, and it probably provided a meaningful source of protein for them.

Fishing wasn’t exclusive to Homo sapiens either. We know this because, in Neumark-Nord in Germany, the remains of Neanderthals from 30,000 years ago were found alongside the remains of fish (replete with scales still noticeable) and crude tools that may have been used for fishing.

Don’t be bored by this information, or should you be, just stay with me. It’s just necessary to set up the more pertinent information.

So far, we’ve discussed subsistence fishing, with relatively crude tools, done in the shallows by people from long ago that left convincing but unintended evidence. Let’s move on to something that more resembles the modern understanding of the act of aquatic calorie-seeking.

The Egyptians clearly show us that they were fishing circa 3500 BCE, a fact we know primarily from extensive artwork and papyrus documents showing us them fishing with spears, nets, rods, line, and even hooks (which, from what we could tell, all appeared on the scene at roughly the same time). The life of the Egyptians revolved around the Nile River, which was full of fish, so it only makes sense that fish became a staple of their diets. They would eat it fresh and dry it to consume later. It was so important to them that fish became a symbol of abundance and fertility, which isn’t far off from what it would later symbolize in Israel due to a certain famous Jewish prophet circa zero to thirty-three AD. The Egyptians would make boats from reeds so that they could fish from out in the Nile and get away from the shore so as to increase their catch. We even have evidence from the 12th dynasty that they used metal hooks with barbs. We also have evidence from China around the same time that they were fishing similarly. It seems for them, it was also an important part of the diets of those who lived near rivers and the ocean.

As with many things that originated in Egypt, the Greeks and the Romans also caught on afterward. They also left us intricate writing about the practice, how they did it, and even how they looked upon the profession. The earliest such work we still have is the Halieutika, a treatise on sea fishing written by the poet Oppian of Corycus.

The means by which Oppian tells us that they went after fish was with nets cast from boats, scoop nets which were held open by a hoop, spears, tridents, and various passive traps “which work while their masters sleep.” Oppian’s description of fishing with a “motionless” net is also fascinating (from NYKDaily.com): “The fishers set up very light nets of buoyant flax and wheel in a circle round about while they violently strike the surface of the sea with their oars and make a din with sweeping blow of poles. At the flashing of the swift oars and the noise the fish bound in terror and rush into the bosom of the net which stands at rest, thinking it to be a shelter: foolish fishes which, frightened by a noise, enter the gates of doom. Then the fishers on either side hasten with the ropes to draw the net ashore.”

What’s important from a historical perspective is that Ancient Greek fishing (and probably most ancient people anywhere) often occurred in lakes or rivers. If it was in the ocean, it is clear that the ancient fishing boats were only used close to the shore. From what we can tell, these fishing boats did not have a mast or a sail. This means that while people certainly tried to get fish for their diets, it is doubtful they could do it in mass from deep waters, instead just catching what they could close to the shore. It is unlikely that they could significantly affect the number of fish in their area or that fish greatly affected their lives. No doubt they enjoyed eating seafood, and no doubt it was important to the fishermen. However, it doesn’t seem necessary for their economy or that they were calorically reliant on fish for survival. Now, this isn’t to say that for coastal communities, it wasn’t an important source of protein. Very probably, it was vital for many communities. But the Greeks also had diverse crops that they grew and numerous types of livestock. Had the fish disappeared for some reason, it’s doubtful there would have been a significant impact on people’s ability to survive or the economy.

Interestingly, from what we can glean from certain writings that have been preserved, fishing and fishermen seem to have been looked down upon by others in society. As it was physically demanding and not very lucrative, it appears to have been a job in which the lower classes would participate. It was a simple and unsophisticated endeavor, and the well-off Greeks always aimed to appear sophisticated. This only helps the argument that it wasn’t an important food source for the population. We think this was true because, in his work Politics, Aristotle describes the classes of his society and mentions that fishermen were of the lowest class. Even in the Odyssey, Homer describes fishermen as simple people who were not the type who would interfere with the lives of important people such as heroes or kings.

As we move into the Roman period, it may be no surprise that things become more gripping, as much about the transition between the Greek and Roman realities did. The importance and prevalence of fish in people’s diets seem to have increased, and the importance of seafood within the overall economy – which would span the entire Mediterranean – is undeniable. These transformations are important. Suddenly, man didn’t see the caloric potential hidden beneath the waves as something that would solely supplement diets dominated by other sources. Nor was it mostly reserved for coastal communities or those living along large rivers such as the Nile. It has now evolved into something bigger. It became important and probably necessary for people of all types and locations and an important part of an economy that would eclipse anything seen before. It also would be the first type of fishing that would look slightly similar to our own, even though, as we will see, it was still different in many fundamental ways.

Within the Roman realm, most of the population began to depend on fish as a noteworthy part of their subsistence. It’s not so much that they relied on fish for the calories, for survival, but for their sense of culture and for what made for a good meal in their eyes. And therefore, along with cereals, wine, and vegetable oil, it became an essential part of the Roman economy. Whether it was preserved or fresh, it seems that fish were served in some form at nearly every table in the empire, especially if one was hosting. The rich sought out the rarest and tastiest types for themselves. At the same time, the poorer seem to have eaten more common types, either dried out or preserved in a way by being transformed into fish sauces.

This author and most within the audience would probably not do well relying on these sauces. But apparently, they were enjoyed the realm over.

We know about four types of fish sauces, but garum was undoubtedly the most popular. It was made – get this – by fermenting the entrails of fish “naturally” and then using salt to keep this process as safe from putrefaction as possible. No part about that translates to me as a natural process for food sourcing. No part about that communicates to me it could be anything but putrid.

Regardless, they would take one part salt, eight parts fish guts (and that can be from any type of fish, from tuna to small river fish), and then dry it in the sun for several weeks, stirring this mix daily. You’d then strain the remaining concoction, which somehow resulted in a clear liquid, which would then be stored in amphorae – the large shipping containers of the way – and shipped to anywhere in the empire. Garum was used as a condiment, sauce, or ingredient in many of the Roman’s favorite staple dishes. It was highly prized but ubiquitous and used by all classes, separated by the quality level. Imagine if there were levels of ketchup one could buy, and which kind you possessed signaled your level of wealth. Of course, one has to imagine the taste of Heinz’s would dwarf whatever garum tastes like. But, again, that could be this author’s perspective on things getting out of hand. Many Asian cultures use similar fish sauces to this day, and some even say that Worcestershire sauce is similar in tastefulness and savory flavor. Although the potential of that comparison being correct boggles the mind a bit…

What isn’t disgusting about the increase in the demand for fish caused by the sauces made from their entrails is the effect this had on the economy and the general circulation of goods, which is paramount for any thriving and stable society – even one as large as the Roman Empire. Fish “factories” were made to meet the demand because commercial deep-sea fishing still had not yet emerged.

A slight pivot now may be helpful. We will continue discussing fishing during the Roman world. Still, we need to move on by discussing humans’ relationship with different types of seafood in general. One of the problems about fishing – which will become even more evident as we move closer to the present day – is that unlike crops or livestock, which are commodities, seafood is usually a resource. No one usually owns it. In most cases, you grab what you can from beneath the waves, and it’s yours.

And yes, we should make note that this wasn’t universally true. In Roman law, there was total or partial ownership of natural resources such as lakes, river sections, or coastal areas. Often, wealthy landowners would also have fishing rights when they owned these resources and, at times, could prohibit others from fishing on their land. But the Romans were also careful to have a lot of public land so that anyone could fish. They even enforced limits on how much people could fish from specific areas to not overfish in that location. They would even grant permits to people for a certain amount of fish. They would issue fines or penalties if you broke the regulations for a particular fishing area. It seems they would even have local officials known as “fishery overseers,” whose job was adequately enforcing the rules.

Two points on that. One, ancient Rome is remarkable in how it can startle one as you look into little things like this, which probably weren’t in your history books or some documentary you have seen. You realize their society’s similarity to ours despite being a couple thousand years ago. They genuinely loved their rules, organization, and efficiency. How they enforced it with their technology and with masses of illiterate people spread out for a long time in an empire stretching from Egypt to Scotland is mind-boggling. It should also be noted that the Romans were not alone, nor the first, in having fishing regulations. The Egyptians enforced fishing regulations on the Nile, and the Chinese did as well in their numerous waterways and coastal areas. But let’s not get too bogged down in the specifics. We must also recognize that their fishing rights system was probably a result of the desire for class and ownership distinction instead of some insight into the ecological dangers of overfishing.

Point two, while the idea of fishing rights and ownership of natural resources existed, seafood was still a resource. It only became a commodity once fish were caught and dead. They were something “out there” in nature to be brought back, not unlike something one might mine out of a mountainside. It was a resource with an inherent value. Commodities are already owned, and their value depends on quality, the market, scarcity, etc.

Understanding the difference between commodities and resources is essential, especially when discussing human attitudes toward fish and fishing. Without realizing it, almost subconsciously, humans treat and care about the classification differently. A fish and a cow are both living creatures that you can eat. Yet one you own for its whole life, you care for it, you may have helped it be born, you feed it, you keep it safe, if for no other reason that if you don’t, it will never be worth any money for you. You may even look it in the eyes. It’s yours! No one treats fish like this (and we’re talking about historically, and in the aggregate, I am sure a blanket statement like that would upset some pet fish lovers out there…). People just don’t view or treat commodities or resources similarly.

This has consequential side effects.

Just as humans usually don’t care about the setting surrounding the mountain, if it contains a valuable resource, we will usually sacrifice all of it and keep at it until we think there is none left. Did this matter too much for the Romans in their time? No, even if they didn’t enforce any regulations, there wasn’t a fear of running out of fish in the big picture. That would have been a laughable proposition to them. Remember the comparison for later…

There is one meaningful way you can alter a human’s relationship with seafood, and that’s where fish farms come back into the discussion. That’s why their arrival was a significant innovation we still employ today. Again, more on that later.

What’s remarkable about our relationship with seafood is that it didn’t change much from pre-history through antiquity. It only made significant changes once humans entered what we’d consider a more modern age. This is genuinely fascinating. Sure, the large empires made rules around it, increased the variety of ways of eating it, and it became more of a staple for certain peoples. The nets and traps got a bit better, and the spears and rods/lines made improvements, but it was nothing monumental. Not compared to the changes in other aspects of life and technology. Mostly, people still fished in similar ways, on the same coasts, rivers, and lakes they had for thousands of years.

The significant change comes with fish farming, also known as aquaculture. Now, there is a slight issue with semantics here. Humans have been creating man-made ponds and lakes to keep fish for eating for a long time. The ancient Romans, Chinese, and Egyptians did this. The Chinese seem to have been the most adamant about it, even having fish swim in their flooded rice patties as a means of fertilization. The Romans would even have fish ponds in their palaces, which were for show and not food. The Egyptians would divert the Nile into walled-off areas to store live fish for eating. Yet, while this certainly is a form of keeping live fish, it isn’t the same as fish farming. While it’s impressive for the ancients, it wasn’t revolutionary in any meaningful way. It did not alter the way the vast majority of people fished or got their seafood.

Some consider the first real fish farms to be in Europe in the 11th century when monasteries and royalty would create large man-made ponds to raise fish, often to eat on Fridays or for other religious reasons. These were very different than what the ancients were doing in many ways. They had sluices, channels, and weirs to control water flow and quality. They made enhanced feeding practices and, importantly, used selective breeding to create desired traits. They were truly farming the fish instead of isolating them in controlled areas to consume later.

This is the truly intriguing thing to take note of. Modern fishing, including highly productive fish farming and fishing techniques that take people past the coastal area and into deeper waters to catch fish at a more industrial scale, is new to both humans and the oceanic ecosystems.

Modern fish farms are recent innovations that seem to have first started in Germany in 1733. This is considered “modern” because the farmer who started this farm successfully fertilized gathered fish eggs and raised the fish that were then hatched for food. So, just like farmers plant seeds, around 300 years ago, humans started interacting with fish eggs, ensuring they’re fertilized so that there is an adequate excess of fish to go to market. It is remarkable that this “technology” took this long to be realized, long after land farmers were breeding plants together to increase heartiness and whatever characteristics they’d like. It is even more remarkable that now fish is one of the most common food sources in the world and that at least half of that input now comes from farms. It all happened so quick.

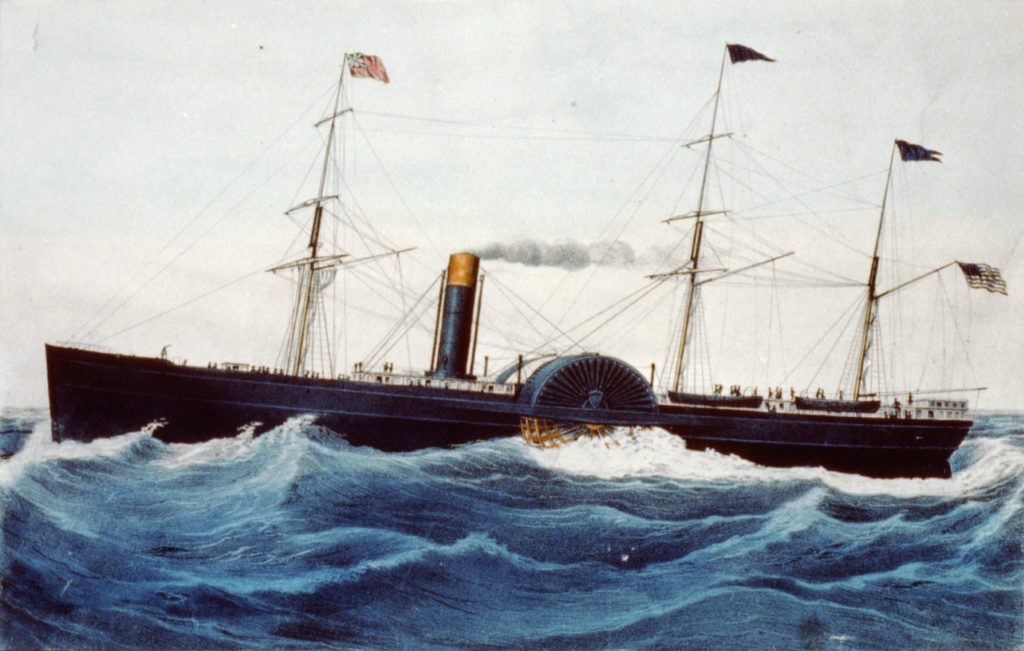

What’s more mentally daunting is what we consider commercial fishing of the “normal” kind, i.e., not from a farm. This also is a new phenomenon. Using large nets to catch fish in deeper waters in a manner just slightly similar to modern times started late in the 1400s. But really, we needed better net technology and, most importantly, steam engines to make this happen in any significant way. After those came onto the scene, we saw the Dutch forming fleets of herring drifters, enabling them to stay at sea for a long while, sending back their catches periodically. Great Britain began to use trawlers in the 17th century but saw the practice take off in great numbers once they didn’t have to rely on the wind.

You see, it was just hard to reliably do this kind of fishing with smaller nets and from boats that were reliant upon the wind. So, what we would recognize today as commercial fishing practices didn’t start in earnest until the 1800s. In addition, it was mechanized winches and newer, eventually synthetic, net materials that allowed these boats to fish where, when, and how they wanted. This outright changed the game. Making massive nets capable of hauling weighty loads and then being able to bring those loads to the boat with ease simply altered man’s relationship .

I am not sure why, but before my research I would have thought that this was done, in some capacity at least, in Ancient Rome. Not the part about steam engines and synthetic nets, of course, but the rest of it. However, large-scale deep-water fishing is a recent revolution. Even when the Romans had a large seafood market, they didn’t practice organized commercial deep-sea fishing. It’s a new thing. While surprising, one has to imagine that this is a good thing because if it started earlier, we would not have the variety of fish available that we do today.

This point about the relative newness of fishing as we think of it today is revealed even more so when you consider recreational fishing, which was only first mentioned in the 15th century in an essay titled “Treatyse of Fysshynge wyth an Angle” by Dame Juliana Berners, the prioress of the Benedictine Sopwell Nunnery. Sure, someone fished recreationally before this, but for it to take this long to be mentioned? Just amazing.

So when someone wants to tell you that the oceans will be alright and that your menu options won’t change because humans have been doing this forever, just tell them about this history. It is new; if we don’t change our ways, it will become a fad in the grand scheme. It will become a thing for the history books and not your belly. Okay, let’s discuss what has been going on recently.

The rest of the story is a bit more predictable and a bit more f-ed up. In the late 19th century, we got the steam engine and the ability to create fishing nets that were from synthetic materials. Throw in the technology to actually haul in these ridiculously massive nets, and we genuinely have a new world. Now, fishing boats, organized into fleets and run by large companies, could go anywhere in the world and stay at sea for extended periods. These innovations increased fishing efficiency (temporarily, at least) and allowed fishermen to explore previously inaccessible waters.

As the 20th century progressed and this technology became available to everyone, commercial fishing expanded into a global endeavor. Eventually, technology advanced even further, fueled by innovations that the world wars brought us. Suddenly, fishing boats had tools their forefathers couldn’t even imagine, such as sonar, radar, GPS, and spotter plans to look for fish from the air. It would be an understatement to say this made locating and catching fish easier. By the 1960s, fishing boats had tools that made their quest somewhat of an unfair fight. Throw in refrigeration, improved transportation, globalization, and increased wealth worldwide, and BAM! Now, any fishing company can export their seafood to distant markets that don’t even need to be near water, and we have a seafood industry that is even more profitable and ubiquitous. The world’s population and taste for fish grew to new heights. This is why the average annual seafood consumption per person has doubled since the 1970s. Unfortunately, the attitudes toward how to treat the oceans’ ecosystems did not evolve enough.

With increased efficiency, eventually, concerns about overfishing made their first appearance. The ability to catch vast quantities of fish led to the depletion of many fish stocks. It became evident that the world’s oceans were not an endless resource, and sustainable fishing practices became a pressing issue. It wasn’t a secret; people could see what was happening and what would happen and began to sound the alarm.

In the latter half of the 20th century and into the 21st century, efforts to combat overfishing gained momentum. International agreements, regulations, and the promotion of sustainable fishing practices began to pop up.

This is when we finally do hear some good news.

In 1994, the United Nations Convention of the Law of the Sea went into enforcement. UNCLOS established the legal framework for managing and conserving living marine resources, including fish stocks, within exclusive economic zones (EEZs) on the high seas. Then, there was the United Nations Fish Stock Agreement, which went into force in 2001. It established principles for sustainable management and called for the precautionary approach to fisheries management. 1975, we got the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). It deals with endangered species and aims to regulate the international trade of certain fish species threatened by overexploitation.

Yada, yada, yada. I could go on. There are more regulations and oversight committees created with excellent aims. And some positive results were seen. The number of fish discards thrown back overboard dead or alive (which we touched upon earlier) decreased from around 13 million tonnes yearly to 8.5 million tonnes annually. While any “millions of tonnes of discarded fish” is too much, at least it went down.

But these results and data points start to get downright confusing based on what you’re looking for.

Consider this information from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). The percentage of stocks fished at biologically unsustainable levels increased from 10 percent in 1974 to 34.2 percent in 2017. However, the data also tell us that maximally sustainably fished stocks rose to 59.6 percent in 2017. This is partly a reflection of the regulations and oversight we discussed. But what does this really mean? This means that both sustainable and unsustainable fishing activities are increasing. How is this possible? Fish farms mostly. And the species that pay the cost are the non-commercial species. We have reached the limit of harvesting fish from the open ocean. Without real sustainability options, we will never see growth in those types of wild-caught fish again.

So, let me make this clear: There have been some improvements, and some people are working very hard to do the right thing. It is not all doom and gloom. Many countries, often in the West, are doing the right thing and monitoring their fishing companies as best they can. But, after looking into this, I came away with some thoughts.

A lot of the growth in the sustainable amount of fish species is due to fish farming. It’s due to many species, those that can thrive in that situation, becoming commodities and not resources. That is great and showcases an excellent way to manipulate personal greed into a communal positive. However, not only are there only a few types of fish this currently applies to (which we will cover in the next episode; stay tuned), but those fish then don’t interact with the massive ecosystem that is our oceans. We lose most of the benefits and positive side effects they provide for the wider world. Remember, we’re almost out of tuna, and that story also happens for other species. With all those good intentions and developments, the percentage of fish stock overfished worldwide between 1974 and 2008 went up from 47.9% to 65.8%.

Another thing is to look at who implements and enforces these attempts to reign in the fishing industry worldwide. The UN usually uses sanctions and slaps on the wrist to try and implement these changes. It’s just too large an issue for them to create real change. Ask Ukrainians what they think about UN resolutions and their sanctions’ effects on their lives. Some countries do have better enforcement off their coastlines. But we need this to be a worldwide effort. Asian countries account for 74.5% of all motorized global fishing vessels, followed by America at 11.9%, Africa at 9.8%, and Europe at 3.4%. This doesn’t reflect the percentages of consumption but just who is doing the fishing. Still, it does give you an idea of who would need to change their tactics first and foremost. But the UN’s reach into these cultures, economies, and ways of life isn’t enough. And maybe that’s not a bad thing. Policing won’t fix the issue, nor should it. This clearly needs to be a bottom-up as opposed to a top-down transformation.

China and the EU have made efforts to not increase their fleets. But this is like saying, “I’m bleeding to death, but maybe it’ll be okay because I stopped the increase in blood loss flow. The blood loss is steady now, I did my part.” No, we’re still bleeding, and we know what bleeding leads to.

It gets all the more infuriating when you consider the 35.2 billion dollars a year in subsidies the worldwide fishing industry receives, with $22.2 billion of that given to activities that enhance capacity. What can the UN do to address that glaring evil statistic?! If there was anywhere to start, one would think it’s with that.

Modern history shows that, clearly, these approaches aren’t working. Consider this. Governments subsidize the fishing industry with all that cash to enhance their capacity. Yet, the effective Capture per Unit of Effort of most countries with fishing fleets is 1/5th its value in 1950. Translation: Fleets must expend 5 times more effort today than in 1950 for the same catch. With all of the technological improvements, it doesn’t mean anything if what you’re searching for isn’t there. And yet, we say through our governments, here’s more money for less fish. Go get it! It’s 100% undeniably insane. And – oh yeah – let’s not forget that all this data I just threw at you is related to worldwide legal fishing. We aren’t even sure what’s happening with illegal fishing data-wise, except that the FAO is convinced it is increasing.

On a website for the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, there is a sentiment that reflects well on my central revelation about fishing: “There is a senseless race to bottom by over-sized fleets seeking to increase or sustain capacity without a clear economic rationale.”

THERE IS NO ECONOMIC RATIONALE. That’s not even considering rationales related to non-economic issues.

Now, I want to circle back to what scares me most about this situation. All this information reveals that this dire situation is unlike any other we face today. This isn’t like global warming. It’s not like factory farming. It’s not like drought, hurricanes, floods, etc. It isn’t even about taking food out of peoples’ mouths. In its potential reach, it stands alone with its potential implications for CO2 increases and O2 decreases, its potential to reshape coastlines, destroy economies, and – we will get to this in the next episode – reduce human health. Of course, who knows what other effects this all could have. All because of fish!

We can’t seem to deal with this situation because we can’t see it in front of us, because it’s happening in our oceans, which 99.9% of us will only experience waist-deep. We can’t address it adequately because it goes deeper than greed, stupidity, or ignorance. That’s why it scares the hell out of me. It comes down to putting tasty food in our mouths and bellies. It comes down to something we all do every day, everywhere. Its menace lies in its unsophistication.

We need a real awakening to address this issue. We can do it, but it isn’t a lamely pithy statement when I assert, “It will take everyone .” It won’t begin with changes concerning big businesses, the UN, greedy a-holes running shady companies, new taxes, rules, or enforcement ideas. It will take everyday people caring about their mouth pleasure choices differently.

Sound weird? Yeah, I think most real awakenings always do sound strange at first.

I would like to end this episode with another story. This one is pretty epic.

“The history of the New York oyster is a history of New York itself—its wealth, its strength, its excitement, its greed, its thoughtfulness, its destructiveness, its blindness, and—as any New Yorker will tell you—its filth.” That quote is from New York, The Big Oyster, by Mark Kurlansky. Everyone seems to use this quote when you look into the story about New York City’s past with oysters. And for good reason.

Here are some more quotes.

Jonathan Swift, the Irish author born in 1667, quipped, “He was a bold man that first ate an oyster.”

Tom Robbins, the American author, reflected that “Eating an Oyster is like French-Kissing a mermaid.”

Yet, it’s Ted Danson, of ‘Cheers’ fame, who’s quote illuminates best. He told us, “Oysters are the canaries in the coal mine of the world’s waters, as they are sensitive to temperature, pollution, and other changes.”

Maybe, though, he should have said people’s treatment of oysters is the canary in the coal mine of the world’s waters. This may be best exemplified by the history of New York City and its oyster population.

This is a story worthy of an episode itself. So, should this brief version entice you, I highly encourage researching it a bit. One can find many websites and even podcasts that examine this fascinating historical story.